Name, Identity, and Subjectivity

Name, as the unique symbol of every human being, is endowed with multiple meanings: family blessing, ethnic identity, the cultural rhetoric, and all of the memories that shape the self-identity and subjectivity during the growing process. It represents the image of us, makes us an individual in this world, although the sense of subjectivity is private recognition rather than an explicit characteristic, and a name could be shared. However, this constructed subjectivity, especially for minority, could collapse in the context of immigration – as I said, the subjectivity that name gives us is highly private, our portrayal in the society is never fully controlled by us, rather, it is the cultural norms that make us the person living in the society. In this western regime of representation, minority’s name no longer can symbolise us, while this loss of self-identity is a racial microaggression that happens to most of the immigrants.

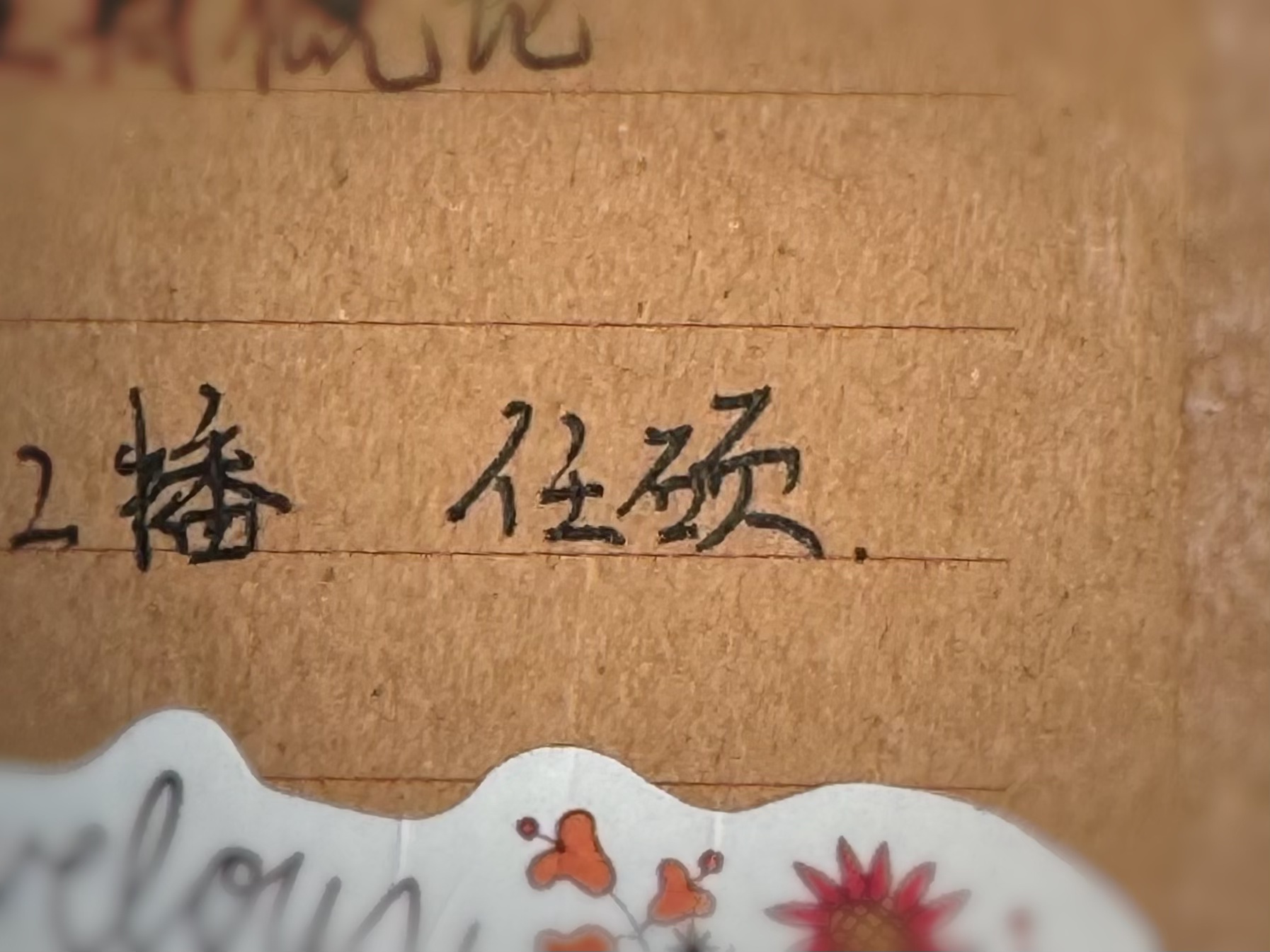

When doing group work, my coworker asked for my name to put on the cover. I gave her my government name “Ren, Shuo” with a comma indicating “Ren” is my surname. “I’m doing the first name first then last name, so I’ll do Shuo Ren, is that correct?” She replied. I don’t really want to be annoying, yet I also don’t want to lose my real name, while “Ren, Shuo” to me is not my name as well. My name is 任硕, two characters, not a bunch of letters in the opposite order. However, I cannot force everyone to add a Mandarin keyboard in their devices just to name me correctly, or let the whole name system conform to Chinese and other people who have a different name format than English. All I can do is listen to teachers speaking our names carefully when doing sign up, and raise my hand when they say “Shuo” that sound like “sure” in the British accent. I made an English name for myself when I was in high school – “Lavio” – a name that no one ever used before, so I don’t have to correct others to call me and explain the tone and order of my name. I always use the terms “surname” and “given name”, because the distinguishing method of first and last is definitely not for Asians. I’m sorry for my sensitivity, but I do feel I lost my name since I came to the Netherlands and simplifying my name into spelling letters is an invisible bully that is already being normalised.

Firstly, what is a microaggression? According to Kohli and Solórzano, racial microaggressions are 1. Subtle verbal and non-verbal insults/assaults directed toward People of Color, often carried out automatically or unconsciously; 2. Layered insults/assaults, based on one’s race, gender, class, sexuality, language, immigration status, phenotype, accent, or name; 3. Cumulative insults/assaults that take their toll on People of Color. In isolation, racial microaggressions may not have much meaning or impact; however, as repeated slights, the effect can be profound.[1] Name is the most significant thing that internalises microaggression: every mispronunciation, alternative made by others, and simplification are disrespectful to the minority. How do I feel when teachers pronounce my name in the wrong way, or when strangers “interrogate” my real name instead of simply calling me Lavio? I would say there has been no serious emotional bursting out and shouting “WHO AM I” (that’s a little too dramatic lol), but something subtle happens within my mind – which can steadily accumulate into identity dislocation.

One day I opened up the notebook I have been using since I was in China, and the cover had my name written in Chinese, which reminds me that I haven’t been called or written in this name for a really long time. But I’m still a Chinese individual, that is the most dislocating thing – I won’t fully become Dutch Lavio just because I live here, while I also don’t feel like being Chinese 任硕because no one ever calls me my real name. Just like a foreign commodity without a label on the shelf, everyone, including the commodity itself, knows what it is, where it is from, and what it is used for. But no one knows its name, the only meaning of its existence is function as a commodity to enrich the diversity of this grocery store. Once it loses its exotic appeal, or becomes too difficult to stock, it will be replaced by something easier. The symbolic violence brought by microaggression can erase identity through negating cultural marks.

“Names can connect children to their ancestors, country of origin or ethnic group, and often have deep meaning or symbolism for parents and families. When a child goes to school and their name is mispronounced or changed, it can negate the thought, care and significance of the name, and thus the identity of the child.”[2]

The fact is, I have so many names, and my friends always make jokes about it. Lavio’s origin sounds ridiculous, it basically just separates viola and puts “la” at the front, because I was obsessed with this instrument when I was young. My social media name is Ribs, ‘cause Lorde has a song called ribs that I really like, and my initials are R.S., which are respectively the first and last letter of these curved arches of bone. Rens is also a name I use a lot, since I know it is a typical Dutch name and very close to my name. About these names, I also cannot tell why I made it: is it because I think it is cool to have a English name and my real name is so lame, or trying to integrate into another culture, or just too lazy to explain how to pronounce 任硕 and why it is that order, or more deeper reasons – the regime of representation, the epistemic violence, the empowerment of my cultural identity, orientalism, oppression and resistance, or, do I really think that much? The complexity of my thoughts makes this reflection harder than I thought.

What is carried by a name? To me, my countless names don’t have any special meaning at all. Lavio and Ribs is a word game, Rens seems meaningful in itself – a short version of Laurens, with a long history in the Netherlands – but I merely notice its similarity with my surname’s spelling. But my real name is different: 任硕, two beautiful squares that are typical Chinese aesthetic for characters. 任 is my surname, meaning responsibility, freedom, and reliability, with a structure visually representing a stable foundation; 硕 is my given name, meaning magnificent, wisdom, with a similar visual structure as my surname. These praises and blessing is not always in my mind, for most of the time, I even feel a bit humbled for having a meaningful name but being so ordinary. But although I don’t keep these precise meanings in mind all the time, I always know it is bestowed by family tie, by my culture, by heaven, with love, which makes me myself in the world I live in. This is something that my anglicised names could never give. Identity, subjectivity, self-recognition, these terms that make us an individual are not merely constructed and maintained by the name spelling itself, but rely on how much emotional effort you put into it. Each name of mine represents the tactical negotiation within me, the self-fragmentation, and the oscillation between objectivity and subjectivity. Struggling with “who am I” and “who should I be” in the Netherlands.

When reading the article written by Kohli and Solórzano, I was curious about the concept they mentioned – “microaggression” which made me reflect: if all of those normalised things they mentioned are counted as microaggression, then what about all of the unremarkable but memorable details that happened in my life? For instance, when my teacher wants to respect my name and ask, “Did I pronounce your name right?”, can this kind question be seen as a microaggression? Since this question somehow makes me a spotlight for a few seconds and they never need to ask the pronunciation of my white classmates’ names. Also, when someone said, “Lavio? I’ve never heard that name, which culture does it belong to?” and “oh you made it yourself? That’s so cool!” Most of them are just curious, and not meant to be aggressive, but still, can I say it’s a bit aggressive? This viewpoint sounds a bit radical, but it reveals the dilemma of how we define this concept, and who manages the right to define it. Is it intention-based or affect-based? Let me be more specific, the definition of microaggression is on the basis of the askers’ intention, whether it is kind or mean, or according to the answerers’ feeling is offended or not?

I would more agree with the affect-based viewpoint. The answerer must carry more affective labour – feeling overwhelmed or frustrated – which represents the existence of personal emotion that is part of the subjectivity. However, we are always taught to restrain these emotions and rationalise the microaggressions as innocent demands. This is the objectifying of us, you can say it is because the social environment makes us feel unsafe to be a distinctive subject, but more importantly, it is this sense of being unsafe that constantly makes us behave modestly, somehow even cowardly. This self-objectification won’t disappear, it will be internalised as a rule within Chinese immigrants and eternally proceed self-supervision and mutual supervision.

Looking back at the content I wrote above, I noticed how many conservative phrases I used: “I don’t really want to be annoying”, “I’m sorry for my sensitivity”, “Lavio’s origin sounds ridiculous.” I still cannot shamelessly position myself as a victim just because I am an Asian living in the Netherlands, but I do feel loss sometimes. That’s why there’s always a war happening in my mind: I am a human who has subjectivity, therefore I think I have the rights to feel offended; while I’m also an immigrant who just a guest sitting in other’s dinner table, so I have to have a good manner and not criticise how weird the dinner’s taste is, all of my sensitivity should be hidden because they don’t mean to bring me that feeling. This tension is a dilemma of immigrants – at least most of the Chinese immigrants – that objectifies them in a country they don’t belong to. Perpetually adapting, apologising, minimising, and the most insidious part? I’ve learned to do this to myself, preventively, before anyone even asks.

[1] Rita Kohli and Daniel G. Solórzano, “Teachers, Please Learn Our Names!: Racial Microagressions and the K–12 Classroom,” Race Ethnicity and Education 15, no. 4 (2012): 447, https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.674026.

[2] Ibid., 444.

Leave a comment