The Analysis of Influencer Dazhi: Why Does She Fail to Be Recognised as Resistance?

This essay is the final assignment from the course “Gender, Intersectionality and Cultural Critique” (YES I FINALLY GOT THE GRADE FOR THIS ESSAY) This is a theoretical reflection of “The Queer Art of Failure” & case study of a Chinese influencer. Since this essay got a positive grade, I think MAYBE I can post it on my blog and not feeling shameful for my sloppy writing… Anyway! Hope it makes sense enough!

“Dazhi”, a Chinese influencer, is known for creating content that goes against menstruation stigma and body shaming. However, she has gained a negative reception in general, with her actions being dismissed as “exaggerated”. Notably, she is cancelled by both male and female audiences, which is a rare example of cross-gender consensus in the context of China’s polarised gender discourse. Her practices appear to resist mainstream aesthetics and refuse to be a “decent woman”, but fail to be recognised as feminist resistance, instead, being simplified as sensationalism. By rejecting the cultural norms and failing to obtain audience approval, Dazhi can be interpreted as “failure” according to J. Halberstam, which can be recognised as a way of refusing to acquiesce to the dominant logic of power and discipline, as well as a form of critique and reveals other possibilities beyond the social norms.[1] This raises a question: why can she be analytically interpreted as “failure”, but fails to be socially recognised as resistance? This paper argues that Dazhi embodies the aesthetics of “failure”, but the “failure” fails at the level of social recognition – due to the absence of a mechanism that decoding such aesthetics. This case also reveals a theoretical limitation of Halberstam’s framework: its emphasis on symbolic interpretation risks neglecting the social conditions required for “failure” to function as a political intervention

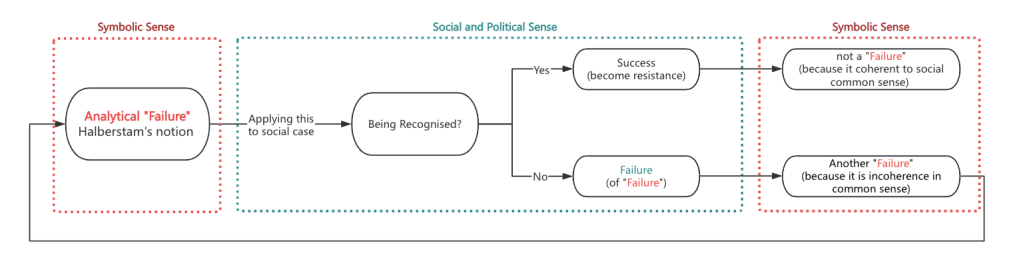

Dazhi’s “failure” is not merely a matter of negative public perception of declining popularity, but rather a structural position that challenges normative frameworks. Based on the anticapitalist and queer perspectives, Halberstam’s notion focuses on failure’s refusal of legibility, the aesthetics of unbecoming and imagines other goals for life.[2] While Halberstam discusses how “failure” can transform into an oppositional tool through “practicing failure”, his framework remains predominantly symbolic, lacking attention to the material and social mechanisms that allow such transformation to occur, or fail to occur. To empirically apply this theory, I propose a three-stage model: (1) analytical failure – the subject violates social norms and is labeled as “failure”; (2) aesthetic practice – the subject actively practices failure to amplify the aesthetics; (3) recognition and transformation – failure is successfully identified as resistance and gains political effect. Dazhi achieves stages 1 and 2 but fails at stage 3, thus unable to transform her embodied practice into recognised resistance. While Halberstam’s framework helps identify her as a “failure”, it cannot explain why this “failure” fails to be recognised at stage 3. To analyse this gap, I will use the concepts of Donna Haraway’s “situated knowledge”[3], Willemijn Ruberg’s “embodiment”[4], and Sara Ahmed’s affect theory to examine the failure of “failure.” Finally, Dazhi’s case exposes a fundamental mismatch between Halberstam’s theoretical context and empirical application, which raises a paradox that I will critically reflect on.

In stage 1, Dazhi’s practices can be read as “failure” on two levels: on the inside, her videos deliberately violate menstruation stigma; on the outside, these violations provoke aggressive responses that mark her as deviant. In stage 2, her over-performance of menstrual visibility captures the inconsistency within patriarchal discourse, turning “failure” into an oppositional tool.

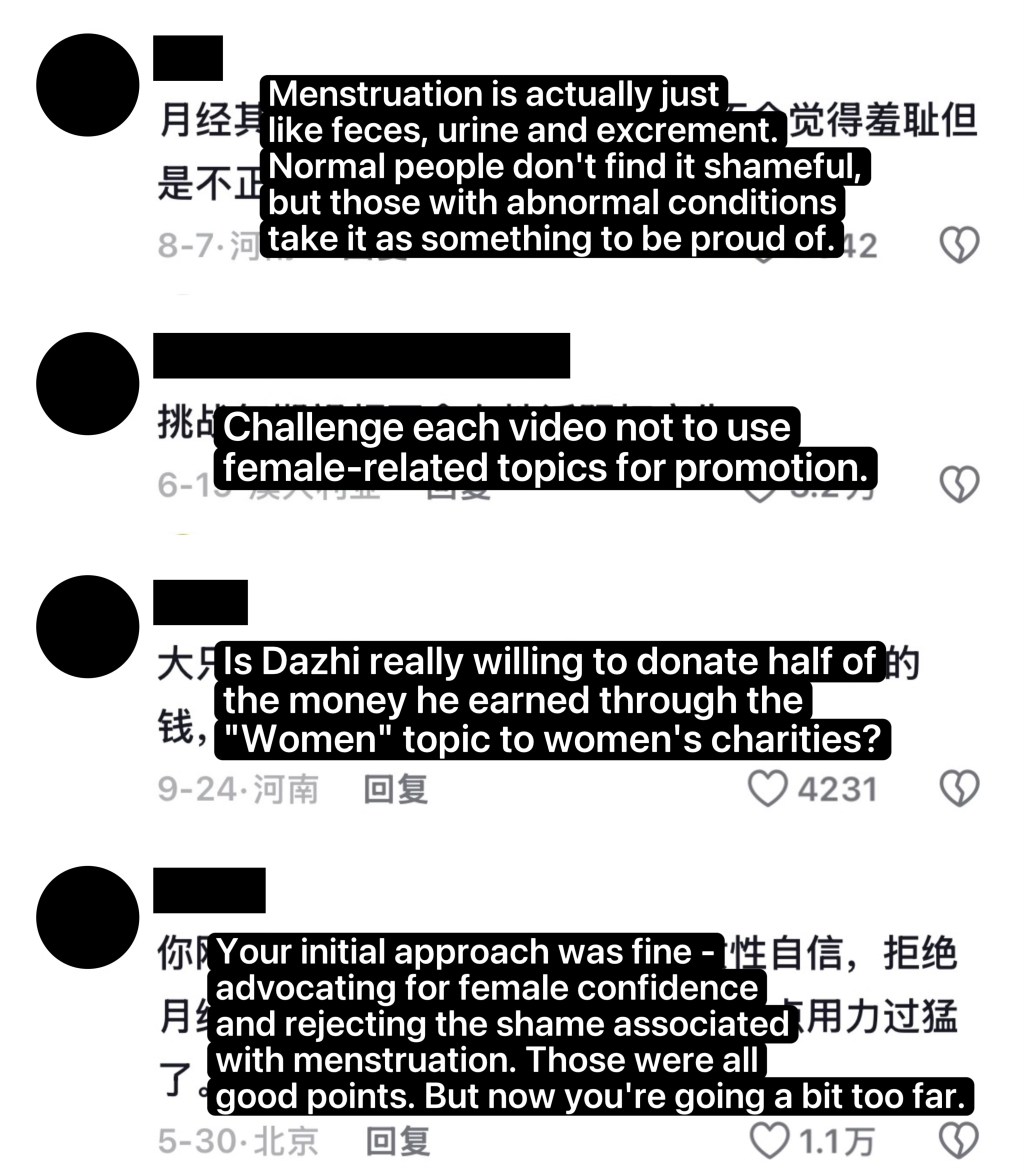

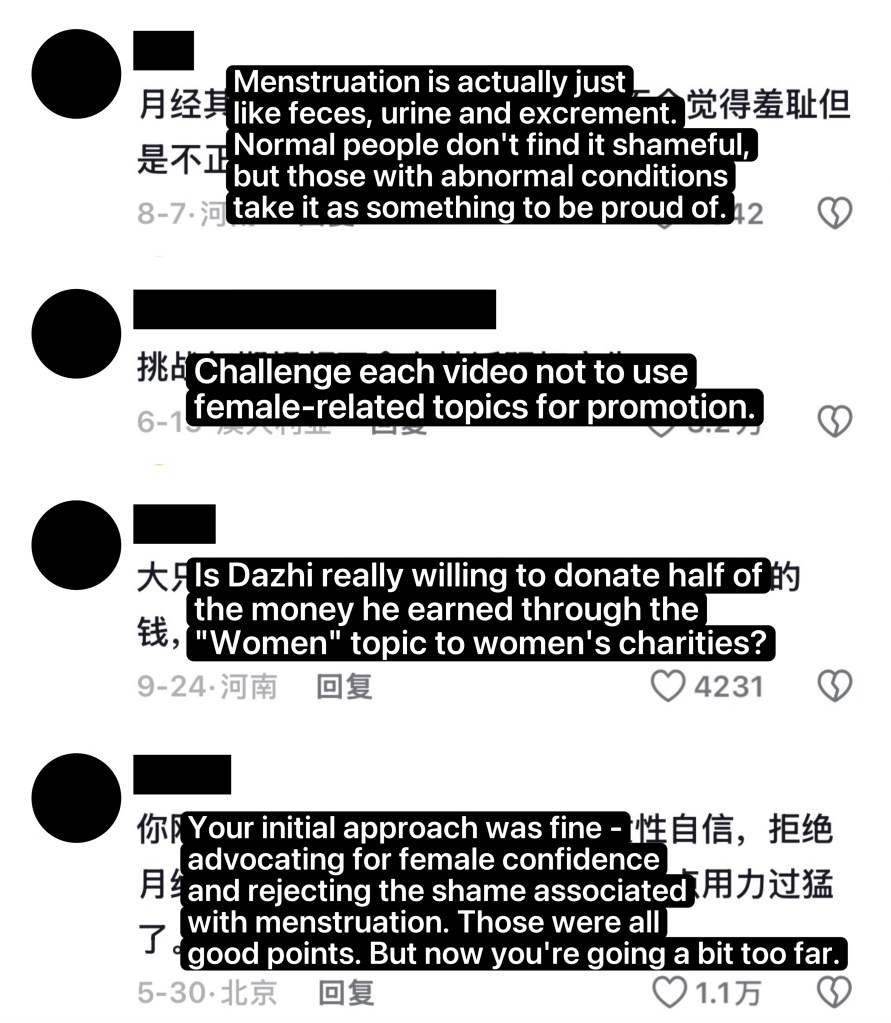

In the context of China, menstruation remains stigmatized. A majority of people use black shopping bags to hide menstrual pads when purchasing them; people of all genders habitually use the term “auntie”(大姨妈) to avoid directly saying “menstruation” – a word considered explicit. While Dazhi actively disrupts these norms: as shown in Figures 1&2, she hangs a sign saying, “I have pads, come and borrow them from me” and distributes free pads to every woman passing by; her white pants are visibly stained with menstrual blood, but she refuses to hide it and continues to film as if the leakage were normal. In a discourse that demands menstruation concealment, her videos embody a refusal to be a silent menstruator – making hyper-visible what is supposed to remain hidden. Furthermore, audience responses construct her as a “failure”. Figure 3 shows typical reactions: viewers label her actions as “abnormal”, “sensational”, and “exaggerated.” Since the majority uphold the traditional framework, these hostile reactions confirm that her practices have successfully disrupted cultural norms. In stage 2, Dazhi’s “failure” aesthetics functions to expose the internal contradictions of patriarchal logic. By making menstruation hyper-visible, her practices reveal a paradox: while the patriarchal discourse insists that women should be “charming”, “visible” and “available to the male gaze”, their physiological phenomenon – menstruation – is paradoxically required to be “invisible” and “embarrassing”. As Halberstam mentioned, failure practice recognises that alternatives are already embedded in the dominant and power is not consistent, therefore, “failure can exploit the unpredictability of ideology and its indeterminate qualities.”[5] Dazhi’s over-performance of menstrual visibility precisely targets this gap, the impossible demand that women be both seen as sexual objects and unseen as menstruating bodies. Nevertheless, the interpretation of her “failure” requires the theoretical lens I have applied. For the majority of her audience, her practices remain merely “disgusting” or “abnormal” videos, they fail to be decoded as political critique. In other words, while Dazhi obtains “failure” aspects (stage 1) and achieves aesthetic level (stage 2), she fails to reach stage 3 – the stage of social recognition and transformation – due to the enabling conditions for such recognition being absent.

To clarify, the previous analysis of Dazhi as “failure” operates within Halberstam’s symbolic framework, whereas stage 3 – which examines recognition – shifts into the empirical realm of social reception. Because her “failure” aesthetics remain unrecognised by audiences, they do not function as resistance but instead reinforce her negative image. This failure of recognition roots from three interrelated layers: Dazhi’s contradictory embodiment, the affective barriers it triggers, and the situated knowledge gap that prevents decoding.

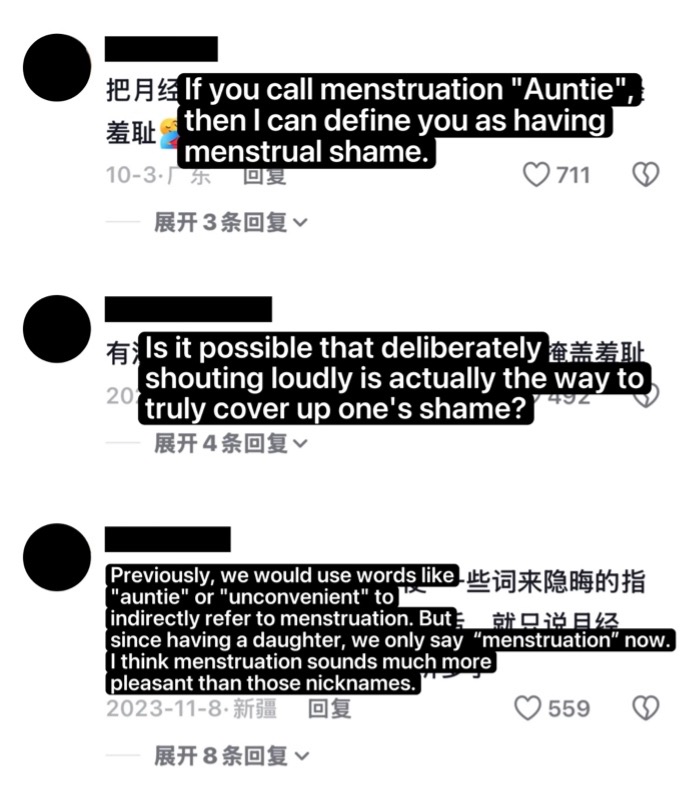

Embodiment – the process that individuals appropriate or reject the cultural norms through bodily practice[6] – is essential to understanding Dazhi’s contradictions. In an early video (Figure 4), she shouts out “there is nothing embarrassing!” while simultaneously using the metaphor “auntie” to imply menstruation. This contradictory embodiment, in the public perspective, is interpreted as “hypocrisy”, “dishonesty” or a “persona collapse”. In a cultural context that demands coherence between words and action, such contradictions decrease her credibility and provoke disgust – an affective barrier to further engagement. When discussing the “disgust” feeling, Ahmed uses the term “sticky” to theorises that, when the word “disgust” is repeatedly used to describe a body, this attribution becomes intrinsic to that body, and the body itself becomes a “sticky body” – one that automatically evokes “disgust” even without explicitly invoking the word.[7] This video has become sticky in Dazhi’s online circulation: it is repeatedly invoked as evidence of her dishonesty, sticking her image as a “disgusting body”. Once Dazhi becomes this “sticky body”, the visceral disgust she evokes blocks rational engagement. Even if viewers could conquer the visceral barrier, their interpretation of Dazhi’s practices remains constrained by their social positioning. Most viewers occupy positions that embody mainstream norms, while from this position, Dazhi’s contradictions are categorised as deviance. Recognising her practice as “failure” aesthetic requires an interpretive framework that can decode unconventional, oppositional styles as critique rather than mere deviance, and the framework is often, but not exclusively, grounded in academic discourses like queer theory. Without such positioning, Dazhi’s “failure” remains invisible, collapsing back to familiar categories of “abnormal”. However, my own identification of “failure” is equally situated – the media studies framework allows me to see strategic incoherence where others see dishonesty, but as Haraway reminds us, “the knowing self is partial in all its guises, never finished, whole, simply there and original.”[8] This vision is also partial and merely reflects my academic standpoint, not Dazhi’s intentions or her audiences’ experiences. This three-layered analysis reveals that Dazhi’s incoherent embodiment operates at every level. But this incoherence possesses double meanings. In his symbolic context, incoherence is not a weakness but the core of “failure” as resistance. Thus, symbolically, her contradictory embodiment constitutes successful “failure”. However, in the empirical sense, this same incoherence reinforces rather than resists her stigma.

To analyse the paradox, firstly, we need to distinguish two kinds of “failure” in the analysis above: analytical “failure” (with quotes) – what Halberstam conceptualises as “the queer art of failure” in a symbolic sense; empirical failure (without quotes) – practices that remain unrecognised as resistance in social and political terms, despite embodying “failure” aesthetics.

Figure 5 illustrates the theoretical paradox embedded in this framework. When a practice is identified as an analytical “failure” and applied to an empirical social context, two potential pathways emerge. If such “failure” practices remain unrecognised (the “No” pathway), they refer to empirical failure, unable to transform into political resistance. When we bring the empirical result back to the symbolic framework for theoretical verification – aiming for self-checking the feasibility of application – a paradox is revealed: a circular trap of “eternal failure”. As indicated by the circular arrow in Figure 5, when empirical failure is brought back into the symbolic framework, it is recoded as another instance of “failure” due to its ongoing incoherence with norms, and then returns to the starting points of the cycle. If this pattern repeats the subject remains trapped in an endless loop of being interpreted as “failure” without ever transforming into resistance. Conversely, if such practices were to be recognised as resistance (the “Yes” pathway), they would gain social legitimacy, but this recognition would simultaneously mean they are no longer incoherent with social norms, thus ceasing to be “failure” in Halberstam’s symbolic sense. The two pathways expose the core paradox: to be recognised as resistance, “failure” must become legible and thus cease to be “failure”, but to remain “failure”, it must stay unrecognised and thus cannot function as resistance. Why does the paradox arise? Ultimately, the reason for these theoretical gaps lies in the mismatch between Halberstam’s original context and the empirical application attempted here. When Halberstam discusses “textual darkness”, he implies the symbolic orientation of “failure” theory:

“It is this understanding of “textual darkness,” or the darkness of a particular reading practice from a particular subject position, that I believe resonates with the queer aesthetics I trace here as a catalogue of resistance through failure.”[9]

The keyword here is “catalogue”, which implies that Halberstam’s discussion is collecting and categorising diverse forms of “failure” as aesthetics, rather than analysing empirical social resistance. However, this orientation excludes the material conditions and consequences of these practices. In his discussion of the “weapons of the weak”, Halberstam mentioned an example of “Scott’s work to describe subtle resistance of slavery like working slowly or feigning incompetence” [10] to demonstrate that passivity can be seen as resistance, but he avoids foreseeing the consequences: these actions could result in punishment or even death, revealing that what is labeled as resistance may fail to achieve in reality. Despite these limitations, Halberstam’s framework remains valuable for its capacity to identify and interpret resistant aesthetics that operate outside mainstream recognition. Therefore, it is necessary to modify it by supplementing the conditions and mechanisms through which “failure” can or cannot be recognised and transformed into political resistance in empirical contexts.

In conclusion, Dazhi’s case can be analytically identified as “failure” while remaining unrecognised by viewers. More importantly, analysed through my three-stage model of applying “failure”, this case exposes the limitation of Halberstam’s “failure” framework: as an insightful theory for analysing the incoherent images within society, “failure” theory lacks the concentration on empirical application, thus it lacks a functional mechanism to realise the political potential that Halberstam attributes to “failure”. Although this case study identifies the need for a supplementary framework, it does not resolve this gap, a concrete framework for systematically applying “failure” as an analytical lens in social and political contexts requires further development. Moreover, this analysis focuses on one case within a specific cultural context – whether similar dynamics operate across different genres, cultures, and topics remains a question. The failure of “failure”, then, is not Dazhi’s own failure, but a theoretical problem that demands further attention.

[1] Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 88, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394358.

[2] Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, 88.

[3] Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599, https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

[4] Willemijn Ruberg, “Body History,” in Gender: Nature, ed. Iris van der Tuin (Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2016), 3–15, Gale eBooks (accessed October 25, 2025), https://link-gale-com.utrechtuniversity.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/CX3644300011/GPS?u=utrecht&sid=bookmark-GPS&xid=2d0424ca.

[6] Ruberg, “Body History,” 11.

[7] Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9780748691142.

[8] Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 586.

[9] Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, 97.

[10] Ibid., 88.

Leave a comment